Optimizing Endurance Running Performance and Rehabilitation: A Q&A with Paul Wilson

Available in:

EN

In this Q&A, Paul Wilson, PT, DPT, OCS, ATC, CSCS, CMPT, shares how he integrates ForceDecks and DynaMo to set rehabilitation guidelines and benchmarks for distance runners using objective force metrics.

What are the most common misconceptions about improving performance in runners?

As a self-sufficient population, endurance runners have long operated outside traditional rehabilitation and performance training frameworks. This lack of resources has led runners to adopt many outdated and suboptimal training plans.

Running injuries are often multifactorial; however, poor training and rehabilitation plans often keep runners in the injury cycle much longer than necessary.

…poor training and rehabilitation plans often keep runners in the injury cycle much longer than necessary.

One of the biggest misconceptions about running lies around rehabilitation for runners. Because running is an endurance sport, runners are often misled to emphasize high repetitions, lighter weights and single leg exercises during their rehabilitation to be more “functional.” However, this approach often fails to provide a sufficient stimulus to get them back to the trail, track or road.

Instead of merely replicating the positions and perceived loads experienced during running, rehabilitation should expose the athlete to additional loading demands to enhance resilience and mitigate overuse injuries. This typically involves heavy resistance training, isometrics, plyometrics and power-based exercises to improve a runner’s force-velocity characteristics.

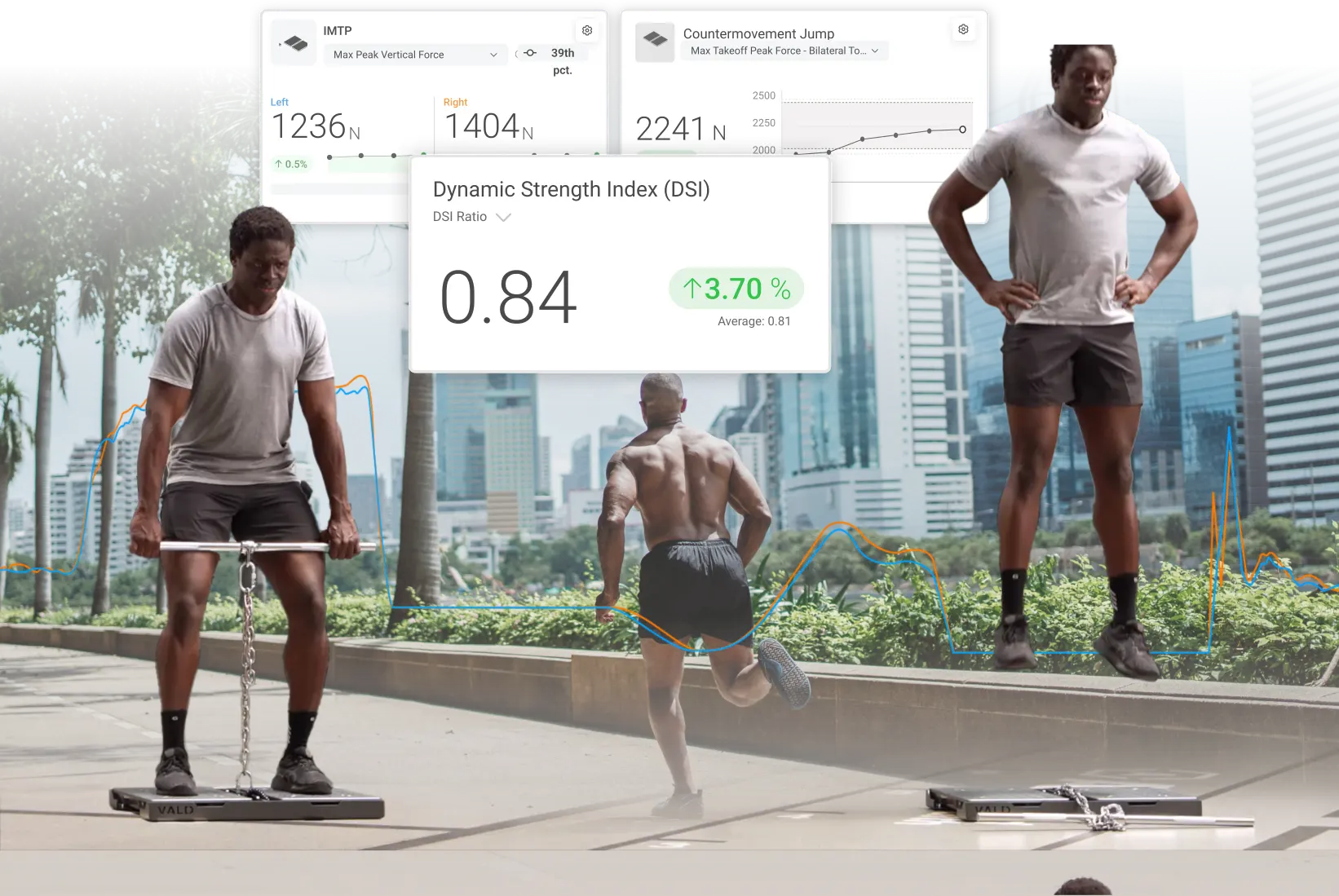

Using simple measures like countermovement jump (CMJ) peak landing force from ForceDecks is a meaningful way to showcase truly how much load a runner can experience from a simple bodyweight activity.

Therefore, incorporating heavy strength and multi-planar exercise helps runners mitigate the monotonous and unidirectional loading schemes that typify running.

…heavy strength and multi-planar exercise [help] runners mitigate the monotonous and unidirectional loading schemes that typify running.

Despite being a “bodyweight exercise,” steady-state running places a substantial load on the lower body, particularly the calf and Achilles. This highlights a common disconnect between the load runners perceive as functional and the high demands required for meaningful adaptation.

[There is a] disconnect between the load runners perceive as functional and the high demands required for meaningful adaptation.

What do you work on to maintain running efficiency, even if your athlete hasn’t been cleared to run?

I try to establish the concept of running economy early in rehabilitation, a term that refers to the energetic cost or efficiency of running at a particular speed. Although running economy is influenced by many factors, two underpinning variables are peak force and rate of force development (RFD).

By increasing an athlete’s peak force and RFD capacity, we dampen the relative load the athlete experiences with each step. This allows the runner to have a greater “strength reserve” when experiencing repeatedly high ground reaction forces (GRFs) over the course of a long run.

By increasing an athlete’s peak force and RFD capacity, we dampen the relative load the athlete experiences with each step.

Maximizing peak force and RFD will also improve running economy by contributing to two key characteristics for running efficiency: stride length and stride frequency.

What tests do you use to establish a runner's strength profile?

I base my training interventions on benchmarked data during rehabilitation to ensure they are adequately prepared to return to running. This involves maximal total body strength, as well as joint-specific strength assessments.

I base my training interventions on benchmarked data during rehabilitation to ensure they are adequately prepared to return to running.

Commonly, I will assess these characteristics through the isometric mid-thigh pull (IMTP) and other joint-specific assessments to better understand an athlete’s running efficiency. Runners often require a familiarization period with the IMTP, which is why I program high-intensity overcoming isometrics in rehabilitation prior to testing.

| Category | IMTP Peak Vertical Force / BM |

|---|---|

| Suboptimal | <3.0x body weight |

| Good | 3.0-3.5x body weight |

| Ideal | >4.0x body weight |

When runners show low total body strength during the rehabilitation of an overuse injury (e.g., Achilles tendinopathy), I focus on resolving symptoms and building capacity so that the athlete’s maximal strength can be trained once symptoms become more tolerable.

What other assessments do you use to gather more isolated information?

Beyond total body strength, I look at tissue-specific factors associated with running-related injury to guide my test selection.

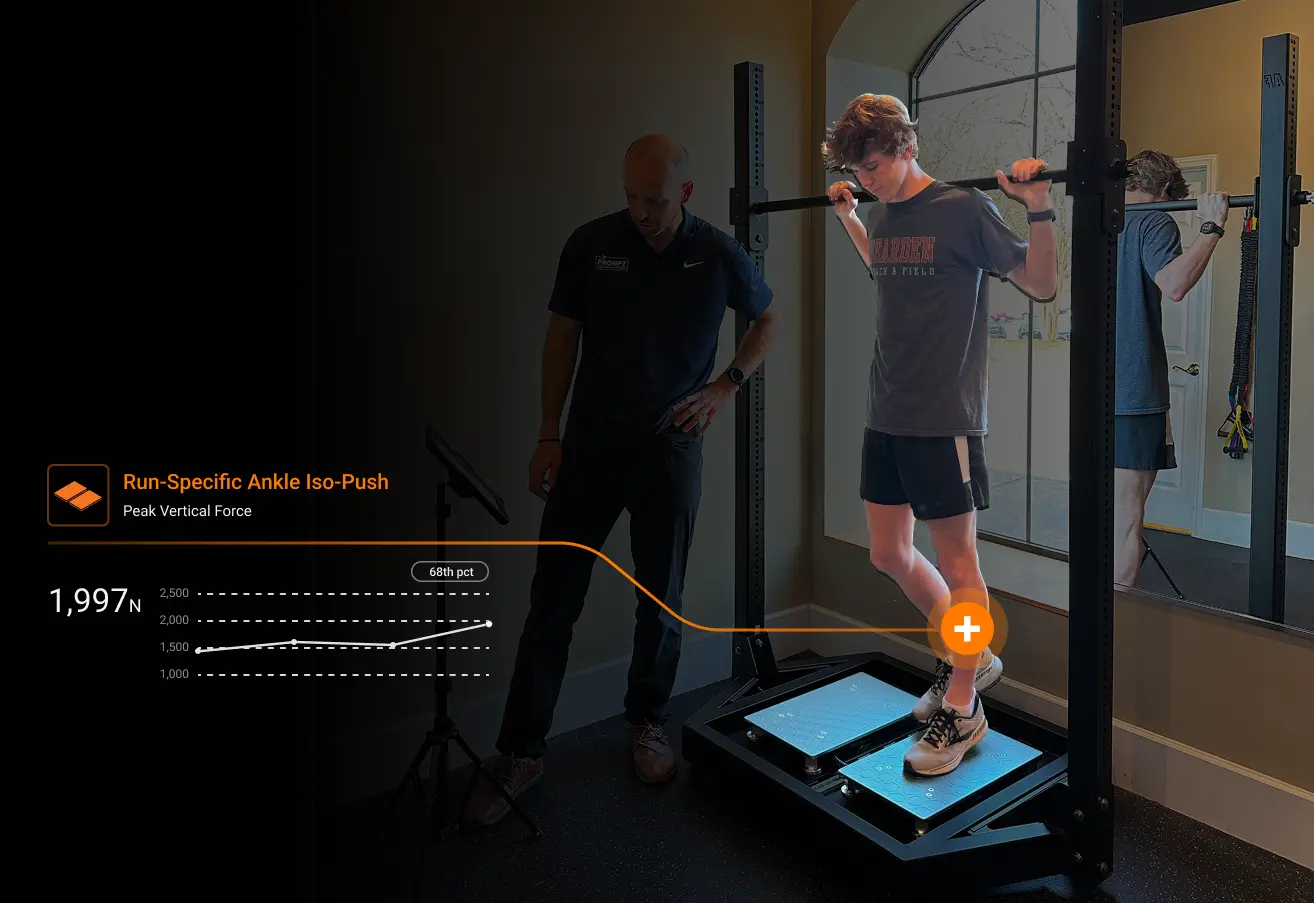

Runners commonly experience tendon-, bone- and joint-related injuries such as Achilles tendinopathy, hamstring tendinopathy, patellofemoral pain and bone stress injuries (BSI). In the presence of these pathologies, I use Run-Specific Isometric Assessments (RSISA) on ForceDecks and assess hip abduction strength using DynaMo Plus to gather injury-specific kinetic data.

…I use RSISA on ForceDecks and assess hip abduction strength using DynaMo Plus to gather injury-specific kinetic data [for injured runners].

From these tests, I look to ensure specific endurance running benchmarks are restored before diving into typical asymmetry thresholds (e.g., <10% asymmetry side to side for “passing” criteria during a return to run program). The benchmarks I use can be found below:

| Category | Hip Iso-Push | Knee Iso-Push | Ankle Iso-Push | Hip Abduction Handheld Dynamometry |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Binary Threshold | 2x system weight | 3.5x body weight | 2.75x body weight | >125N |

Although the treatment of each pathology differs significantly, these benchmarks help to ensure that regardless of the specific injury at hand, the runner is sufficiently prepared to withstand the high-load and volume demands of endurance running.

…these benchmarks help to ensure that…the runner is sufficiently prepared to withstand the high-load and volume demands of endurance running.

Recently, I treated an athlete with a femoral neck stress injury. Once they were safe for testing, I used DynaMo to ensure hip abductor strength had been restored prior to any heavy loading, such as squats or step-ups.

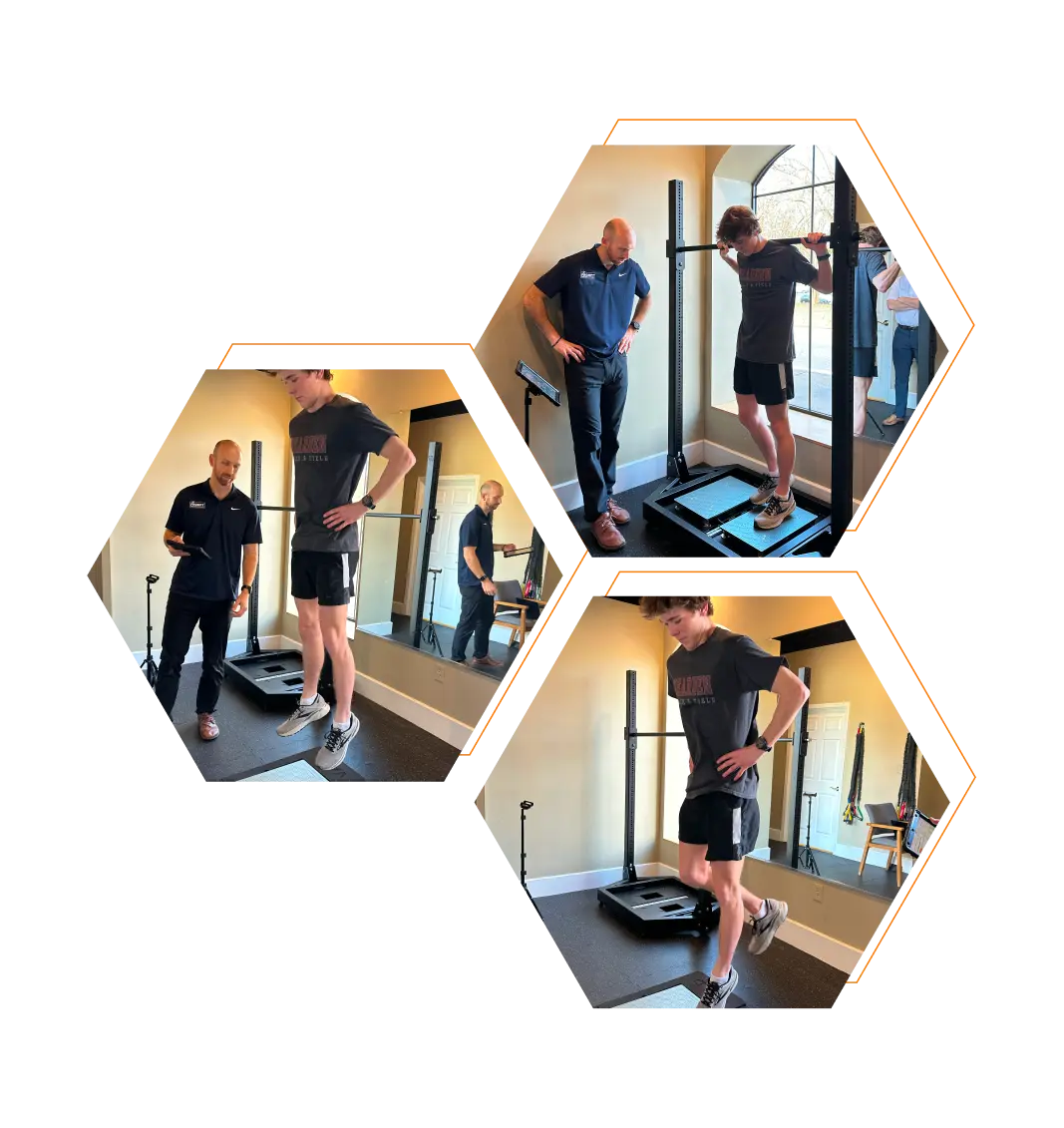

Once we can safely introduce plyometrics after a BSI, I start with double leg tests such as a controlled CMJ or hop test to ensure the athlete is able to symmetrically produce and attenuate load. Typical tissue healing timelines and objective criteria guide progression during rehabilitation. Generally, less than 10% asymmetry is an acceptable threshold for progression to single leg jumping exercises.

Similarly, these benchmarks provide simple directives for rehabilitation interventions. Using heavy, slow sets of 3-5 repetitions, I will preferentially target the specific joints affected with interventions such as the following:

| Region | Hip | Knee | Ankle |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Romanian deadlift Trap bar deadlift Hip thrust Hip Iso-Push | Rear foot elevated split squats Knee Iso-Push Seated knee extension Squat variations | Isometric calf raise Heavy isotonic calf raise (seated & standing) Ankle Iso-Switch |

Resistance training options for endurance runners.

What do you look for if someone has already met the relative strength criteria?

Although it’s rare, seeing runners who exhibit high relative strength numbers (e.g., >4.0x body weight IMTP) informs my rehabilitation process to focus less on peak force and instead use compound assessments like the dynamic strength index (DSI) to learn more about how well they utilize that force.

Using previously established and accepted ratios for the DSI has served as a great benchmark for runners during rehabilitation. In these scenarios, if an athlete presents with a DSI below 0.6, I start integrating more plyometric training to improve their jump efficiency and performance.

However, runners often have low maximal strength values and benefit greatly from heavy-slow resistance training, making the DSI an assessment I use only when necessary.

What assessments do you use for dynamic and reactive strength?

ForceDecks have been a very useful tool for jump profiling with runners. As an athlete begins returning to their pre-injury running volume, I conduct a series of jump tests to ensure readiness.

The CMJ and hop test have been useful to evaluate runners’ plyometric capacity in both slow (>250ms) and fast (<250ms) stretch-shortening cycle (SSC) tasks.

[I use] the CMJ and hop test…to evaluate…both slow (>250ms) and fast (<250ms) SSC tasks.

For the hop test, I evaluate reactive strength index (RSI) and ground contact time (GCT) to measure rapid force tolerance and production. Because GCT influences RSI, I set simple GCT thresholds to ensure RSI accurately reflects fast SSC capacity. Without this check, runners may compensate by increasing jump height through longer GCTs, making GCT a crucial filter for interpreting RSI.

| Category | GCT | RSI |

|---|---|---|

| Suboptimal | >250ms | <2.0 |

| Good | 200-250ms | 2.0-2.5 |

| Ideal | 180-200ms | >2.5 |

Having suboptimal RSI values and GCTs shows a lack of preparation for fast SSC capacities. With this information, I shift away from heavy strength training and focus on plyometric training. I normally include the following interventions during my end-stage running rehabilitation:

- Double leg pogos

- Single leg pogos

- Drop jumps

- Single leg drop jumps

- Bounding

[During end-stages of rehabilitation] I shift away from heavy strength training and focus on plyometric training.

Given the volume of single leg dynamic activity that runners participate in, it may come as a shock to hear that fast SSC plyometric capacity is often limited in this population. Therefore, when prescribing plyometrics for runners, I tend to start with regressions such as bilateral pogos or band-assisted variations before introducing single leg pogos with fast GCTs.

Running test battery of CMJs, single leg jumps (SLJs) and the Ankle Iso-Push assessment.

How are you communicating your findings to your clients?

The classic tropes of many endurance athletes are that they resist strength and plyometric training in rehabilitation. However, I’ve found that visualizing strength and plyometric progressions, such as using graphs and Norms in VALD Hub, allows athletes to see their progress first-hand, improving buy-in exponentially.

While injuries are far more complex than a single strength test or asymmetry result, providing athletes with data about their bodies helps them buy into a rehabilitation plan that puts them on the right path forward.

Rather than continuing to try the same low load or passive interventions to get back to running, they appreciate the need for quality strength improvement, further dispelling the common misconceptions about distance runners.

By integrating force plate assessments, clinicians can take the guesswork out of running rehabilitation and performance training. Assessments like the IMTP, CMJ, hop tests and RSISA provide a comprehensive profile of a runner’s strength, asymmetry and force production capabilities – ultimately guiding more effective interventions.

If you want to learn how VALD’s human measurement technology, including tools like ForceDecks and DynaMo, can support effective running rehabilitation and enhance your athlete’s return to peak performance, explore our Practitioner's Guide to the Calf & Achilles Complex. For more information or to integrate VALD technology into your practice, reach out here.