The Data Informed Future of Healthcare: Intelligence-Based medicine

Available in:

EN

Nicol is a physiotherapist who works within the Irish Rugby High Performance Unit as part of the medical team managing player health and injury risk. He completed a PhD in Health Sciences at Ghent University, Belgium titled “Risk factors for hamstring injuries in professional football players.” He’s also a Former member of the Aspetar Injury and Illness Prevention Programme (ASPREV).

Nicol also holds the role as deputy editor and an editorial board member of British journal of sports medicine (BJSM).

As a clinical researcher with a special interest in injury prevention, Nicol has a great appreciation for integrated healthcare and Evidence-Based medicine. He’s enthusiastic about the role of social media in the dissemination of scientific evidence and research knowledge to everyone. In this blog, Nicol shares his insights into the evolution of healthcare from Evidence-Based Practice to Intelligence-Based Practice.

Intelligence-Based Practice: The Data-Informed Future of Healthcare

Adam was an elite track and field athlete, and in an innocuous routine warm up at a track meet, he suffered a proximal hamstring tendon tear. It was a big deal. His season was ruined, and he would need to get back for a major event in the next season, with a big sponsor contract on the line.

After much debate and a very thorough shared decision-making process, we ended up going conservative (no surgery). I was nervous, but excited about the journey with him. He did well initially, really progressed without much difficulty through the early part of the rehab. We were using our hand-held dynamometer, inclinometer, and subjective feedback as reassessments to determine what each session would look like.

But, after six weeks we were stuck. He was running with no issues, but he still had a 30% strength deficit when I tested him in outer range. It really bothered me – it didn’t make sense, and I was cautious about progressing his running. Then, a senior physio and mentor suggested we do a bilateral strength test on the NordBord. I wasn’t sure, but we needed to shake things up.

We got the test set up, and Adam did his warm-up. First set… 550N uninjured side, 545 injured side (If you don’t know, that’s pretty good). Second set… he cleared 600 both sides. Third set… same again.

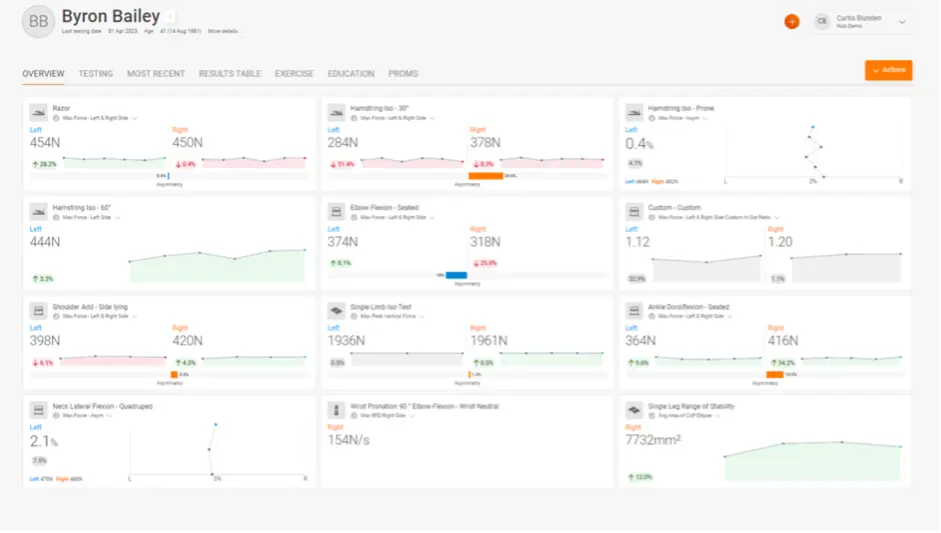

As it turns out, my testing position mimicked his injury mechanism, and because of that, he was anxious and holding back. But the feedback from the NordBord test and the results put him right at ease. Next outer range strength test – deficit gone. Now don’t get me wrong, our measurement tools had put us in a great position to help this athlete achieve his goals. We had baselines to compare against, we had performance metrics to benchmark progression, we had training load data. But I’ll never forget how we were able to use these very same tools to put the athlete (and myself) at ease and create feedback for a motivated, relaxed, and focused approach to getting him back to competition. (He qualified for the Olympics that season). We are at the frontier of a new era in healthcare. And it has already begun.

I’ll never forget how we were able to use these very same tools to put the athlete (and myself) at ease and create feedback for a motivated, relaxed, and focused approach to getting him back to competition.

Where Have We Come From?

In the early 90s, the idea of Evidence-Based medicine was popularized by David Sackett. 1,2 In response to limitations in the understanding and use of published evidence, the Evidence-Based medicine movement’s initial focus was on educating clinicians in the understanding and incorporating published literature to enhance clinical care. While recognising the limitations of evidence alone, Evidence-Based medicine has always stressed the need for including practitioner experience and patient’s values. 3 Evidence-Based medicine’s enduring contributions to clinical medicine include placing the practice of medicine on a solid scientific basis. And to do that, we need to understand how to digest new research findings, but also have intelligent and intuitive tools that help us collect objective data which informs our clinical reasoning.

Firstly, the amount of scientific data being published is now beyond the capability of any human to consume. We simply cannot keep up.

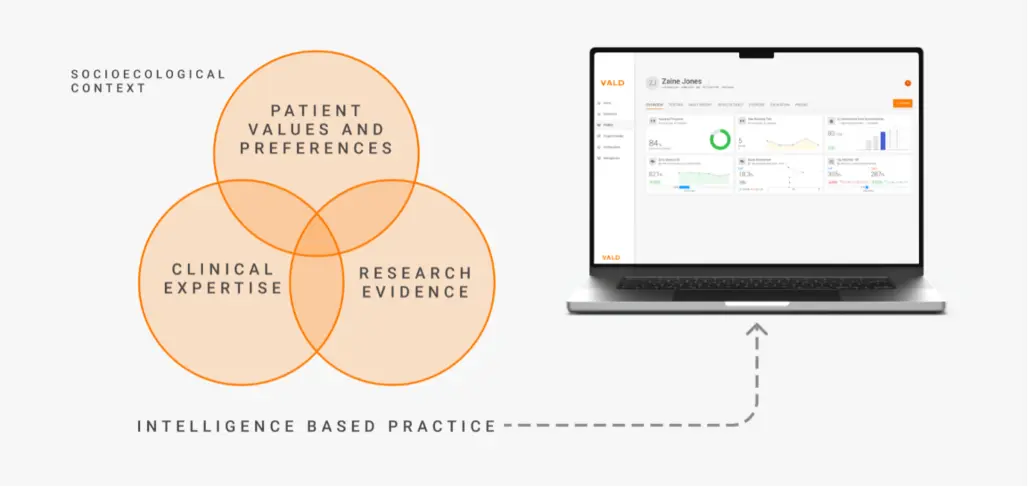

Evidence-Based medicine is best defined as integration of the best research evidence (published literature, most often now clinical practice guidelines and systematic reviews) with clinical expertise (experience and intuition of the clinician) and patient values. 3 The extension of Evidence-Based medicine that is more relevant today is Evidence-Based Practice (EBP), which considers the healthcare setting and circumstances in which we practice. Simply put, EBP is a combination of published scientific evidence, clinical expertise, and patient values (preferences and beliefs that the patient brings to the encounter).

Secondly, relying on my clinical experience and intuition opens the door for bias and convenience. As much as we’d like to believe we stay free of influence, it is the human condition to for these heuristics to influence our reasoning.

But problems have arisen with this approach. 4 Firstly, the amount of scientific data being published is now beyond the capability of any human to consume. We simply cannot keep up. And the advances of machine learning and artificial intelligence, popularized recently by the phenomenon of ChatGPT, emphasizes this.

Secondly, relying on my clinical experience and intuition opens the door for bias and convenience. As much as we’d like to believe we stay free of influence, it is the human condition to for these heuristics to influence our reasoning. I have been a clinician for the better part of two decades and one of the biggest pain points in my practice is that when I see a patient for a session, I have to remember what their results were last week, or check a file, or check my WhatsApp history for the last time the patient reported something to me. Even checking my notes can be a hassle, as they’re often kept obscurely in some sort of management system (i.e. often still free-text boxes, or worse – pen and paper).

When I see a patient for a session, I have to remember what their results were last week, or check a file, or check my WhatsApp history … Even checking my notes can be challenging.

And lastly, patient values are obscured by the nature of our interactions. Instead of creating space and time for this interaction to take place, we are in front of a screen typing notes, reviewing results, or checking schedules without being present. We have traded the value of a trusting relationship and therapeutic alliance for ease of scheduling and payment. We should take care in attending to our patients, and we know that by listening and communicating clearly, we are able to provide better outcomes. However with limited time in the clinical encounter, in part due to our practice of how we gather information, we often don’t really connect. But these frustrations are also opportunities to understand how technology can be leveraged in our daily practise, and in our overall service delivery to our patients.

With limited time in the clinical encounter … we often don’t really connect. But these frustrations are also opportunities to understand how technology can be leveraged in our daily practise.

Intelligence-Based Practice

The proposal of Intelligence–Based Practice (Figure 1) sits squarely on the enormous work that has gone before into EBP. Intelligence-Based Practice now adds technology in a way that keeps up with the current space of knowledge overload that we are in, but also removes some of the burden we have experienced and continue to experience, regardless of new management systems or electronic medical records.

If we allow data to be captured in real time, measurements embedded in our clinical practice, and notes to be auto populated from these methods, we will create space and time again to connect with our patients. We will remove the bias so often impossible to recognize ourselves and allow for a data-informed decision-making process.

If we allow data to be captured in real time, measurements embedded in our clinical practice, and notes to be auto populated from these methods, we will create space and time again to connect with our patients.

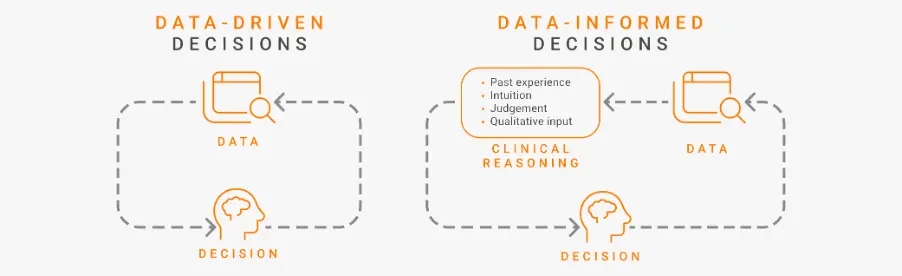

Important to differentiate, this is a data-informed, not a data–driven, process (Figure 2). For the team at VALD, this has been the direction from the start. The genesis of their first product, the NordBord, was a clinical question: “how do we quantify the Nordic hamstring exercise?” and since then, the driver in each of their product developments or additional tools has stayed true to that theme – putting data in the hands of the practitioner. We cannot and should not replace our clinical reasoning, intuition, experience, or judgement. We are interested in combining objective measurable outcomes and accurate, appropriate data to our decision-making process.

Important to differentiate, this is a data-informed, not a data-driven, process … We cannot and should not replace our clinical reasoning, intuition, experience, or judgement.

As we are now acutely aware, context is key in providing appropriate interventions (which at times means none) and outcomes that lead to better health for our patients. This is important at a person level, a team or social group, organization, or governing body, and for societal or governing structures. Another important distinction to make is between digitization and digitalization. While digitization focuses on converting and recording data, digitalization is about using data to develop processes and change workflows to improve manual systems. An example of this would be using digitized customer data from various sources to automatically generate insights from their behaviour. We can do the same in healthcare, and more specifically, musculoskeletal health.

While digitization focuses on converting and recording data, digitalization is about using data to develop processes and change workflows to improve manual systems.

Three Things Are Required to Make This Change Happen

1. Cultures and context need to be understood

One of my own personal mentors, Rod Whiteley, would say “it’s easier for a clinician to learn statistics than for a statistician to learn medicine.” Now this points to the important first step that is needed – a merging of our clinical culture and the ever-evolving data science world. How we approach problem solving, the reasoning behind decision-making, and the narrative we build for the patient must be contextual. We are not proposing to replace clinical reasoning – that takes time and experience to develop, and – at least for now – is a uniquely human skill. But we are conscious of how data can add enormous value to the process of assessment, reassessment, progression, monitoring, and follow-up (even remotely). Technology will leverage the painstaking part of the process (note keeping, lodging results, keeping track) so we can focus on the stuff that matters – connecting with the patient and delivering the best practice to achieve outcomes.

Technology will leverage the painstaking part of the process (note keeping, lodging results, keeping track) so we can focus on the stuff that matters – connecting with the patient and delivering the best practice to achieve outcomes.

2. Data needs to be improved and shared among stakeholders

The old saying holds true: garbage in = garbage out. If we are to ensure the data we receive are accurate and dependable, data quality must be at the forefront of what we do. We might consider sacrificing a little precision (realistically, 100% accuracy is not always possible) for more oomph (good, reliable and clinically relevant collected on the ground). But poor data with inaccurate and inappropriate methods of collection is potentially worse than no data at all.

Ultimately, we are stronger together. Sharing is caring. And if we are to move the needle, it is imperative that we can tell each other what we do in ways that can translate between settings. I’m not proposing we create all–in, massive open data systems – that has just as many dangers associated with it. However, we do need to be able to get the data in the hands of the practitioners and the patients. We need it to create impact where it matters most – clinical delivery and self–management.

And we are stronger together. Sharing is caring… we do need to be able to get the data in the hands of the practitioners, and the patients. We need it to create impact where it matters most – clinical delivery and self-management.

3. Intelligence (read: data) needs to be learned and orchestrated by humans

When IBM’s Watson started reading radiology images, it caused quite a stir. Would this mean the end of radiologists? Clearly the ability for the artificial intelligence of Watson to engage with millions of MRI results/reports and images is far beyond the capability of any human. But of course, Watson has deficiencies in understanding the contexts of the findings. And even with the current hype around the possibilities of machine learning and artificial intelligence, I cannot see a future where we do not need human interpretation of data and findings in the context of a person, connected to their story, and their humanness.

And even with the current hype around the possibilities of machine learning and artificial intelligence, I cannot see a future where we do not need human interpretation of data and findings in the context of a person, connected to their story, and their humanness.

Summary

I’ll never forget the lessons I learned from helping Adam get back to his best, realizing his dreams of Olympic qualification. The use of technology and leaning into data are no longer add-ons to our practice – they have become an integral part of how we best serve our patients. They will not only create better outcomes and scale the delivery of good service but allow us to evolve Evidence-Based Practice into Intelligence-Based Practice. Perhaps most importantly, it will help us prioritize the one thing we know matters above all – human connection. If you would like to know more about this program or how you could use VALD technologies in your organization to help monitor and manage your athletes, please drop us a line.

REFERENCES

- Sackett DL Rosenberg WM Gray JA Haynes RB Richardson WS. Evidence-based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. BMJ. 1996;3127023:71-72.

- Guyatt G, Cairns J, Churchill D, et al. Evidence-based Medicine: A New Approach to Teaching the Practice of Medicine. JAMA. 1992;268(17):2420–2425. doi: 10.1001/jama.1992.03490170092032

- Achilleas Thoma, MD, MSC, FRCS(C), FACS , Felmont F. Eaves, III, MD, FACS, A Brief History of Evidence-based Medicine (EBM) and the Contributions of Dr David Sackett, Aesthetic Surgery Journal, Volume 35, Issue 8, November/December 2015, Pages NP261–NP263, https://doi.org/10.1093/asj/sjv130

- Greenhalgh T, Howick J, Maskrey N. Evidence-based medicine renaissance group. Evidence-based medicine: a movement in crisis. BMJ 2014;348:g3725. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g3725